Abstract

Previous scholarship suggests higher rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions for law enforcement, compared to the general population, which are hypothesized to correlate with their levels of occupational and organization stress and depression.Occupational stress is induced by the profession of law enforcement and includes sudden and spontaneous emergency calls, scenes of death and suffering, and extreme physical exertion. Organizational stress is created by the organization itself and is often observed through a lack of administrative support that results in the officer feeling abandoned by their department and administration. Finally, it’s important to recognize that the most at-risk officers are detectives in small agencies in the Western part of the United States.

Scholarship does, however, suggest that law enforcement officer stress, from both sources, can be mitigated through training and intervention. From the organizational development perspective, law enforcement agencies across the country would likely benefit from data gathering, analysis, intervention design, evaluation, and sustainment of an intervention focused on reducing officer stress.

Deadly Interventions in Suicide Prevention

Introduction

Suicide continues to kill law enforcement officers at a significantly higher rate than in the general population and is thought to be driven by their increased occupational and organizational stress. As a former law enforcement officer and mental health advocate, this topic is critically important to me. Had I not left law enforcement, and without the resources I had while I was there, I fear I would have become another statistic of the suicide epidemic. There are several organizational development interventions that can be leveraged to save lives.

Literature Review

Risk of Law Enforcement Suicide.

Until the rise of the COVID-19 virus and pandemic, suicide remained the top killer of law enforcement officers in the United States, while it’s the 11th leading cause of death in the general population (Chae & Boyle, 2013). In 2012 the average suicide rate for the general population was 11 suicides per 100,000 people. Comparatively, the law enforcement rate was 39% higher at 15.3 suicides per 100,000 officers (Violanti et al., 2012). Violanti and Steege’s 2021 research, using proportionate mortality ratio data from 1999, 2003-2004, and 2007-2014, showed that law enforcement officers are generally 54% more likely to die by suicide than the general population.

One of the most significant predictors of both attempted and completed police suicides is suicidal ideation which is significantly higher in law enforcement compared to the general population (Violanti, 2004). It is estimated that 13.5% of the general population experiences suicidal ideation compared to 25% of law enforcement officers (Chae & Boyle, 2013). When researching suicidal ideation, “five prominent aspects of policing were associated with risk for suicidal ideation: organizational stress; critical incident trauma; shift work; relationship problems; and alcohol use and abuse” (Chae & Boyle, 2013, p. 91; Violanti, 2004). These aspects are also synergistic and cumulative which greatly increase the odds of suicidal ideation, attempts, and completions (Chae & Boyle, 2013).

There are also significant differences between law enforcement suicides and those in the general population, including the method of suicide. For example, firearms accounted for 52% of all general population suicides, but 94% of law enforcement suicides (Chae & Boyle, 2013). One difference may be the easy access and familiarization that law enforcement officers have with firearms compared to the general population (Violanti et al., 2012).

By the Numbers. Within the law enforcement population, some sub-sets of officers are more at risk of suicide. Comparing occupational subsets, detectives and investigators experienced the most significant risk of death by suicide at 64% higher than the general population. Among race, ethnicity, and gender subsets, the risk of suicide was highest for African-Americans, Hispanic males, and all females. Geographically, the western United States had higher proportionate mortality ratios than other regions (Violanti & Steege, 2021).

The size of the law enforcement agency has been found to have a negative correlation with the rate of completed suicides. Departments with fewer than 50 officers experienced the highest suicide rate of 43.78 per 100,000 officers while departments of more than 501 officers experienced the lowest rate at 12.46 per 100,000 officers (Violanti, et al., 2012). The researchers believe that smaller departments are more at risk for suicide due to the structure of their work. Smaller departments generally have fewer resources, particularly surrounding mental health resources, especially in-house resources. Officers working for smaller departments also must be more generalized to handle a wide spectrum of calls from start to finish without the support of specialized divisions that are available in larger departments. The researchers also hypothesize that officers in smaller departments are more likely to be recognized throughout the community, whether on or off duty. This familiarity may make citizens more likely to respond negatively to them even when they are off duty, out of uniform, and with their families. These factors can lead to occupational stress while at work, at home, or at the grocery store (Violanti et al., 2012).

Law Enforcement Stress

By the very nature of their job, law enforcement officers experience an inordinate amount of stress. Occupational stressors are external events consistent with the general body of law enforcement, such as long periods of inactivity interrupted by sudden emergency responses to traumatic calls, scenes of death, and the fear of being assaulted. Organizational stressors, on the other hand, are internal and vary from organization to organization, but generally include unclear orders, lack of support from administrators, and low morale. Both occupational and organizational stressors have been found to increase police stress (Chae & Boyle, 2013) and depressive symptoms (Allison et al., 2019).

Occupational Stress. Stress is pervasive in law enforcement from the spontaneity and severity of physical demands and sudden life-threatening situations (Russell, 2014). When an officer experiences these events, the stress response manifests in the brain’s hypothalamus, which is also responsible for controlling eating, drinking, hormones, and various organs. As a result, stress can cause physical, mental, and emotional changes (Denhardt, 2016). Physical symptoms can include shortness of breath, auditory exclusion, and tunnel vision. Chronic stress means that mental and emotional changes can co-occur and often include anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Papazoglou, 2017). These symptoms can lead to aggressivity which causes officers to perceive both professional and personal situations as more dangerous than they really are (Queiros, 2013). In extreme cases, stress can lead to workplace violence and/or completed suicide (Denhardt, 2016). It’s clear that stress can deeply impact an individual, and it can also impact an organization.

Over time, this chronic stress can develop into fatigue, which occurs in some officers at most agencies (Vila & Kenney, 2002). The literature is unanimous that police officers in the United States suffer from very high levels of fatigue, which can worsen an officer’s mood and exacerbate their anxiety, depression, impulsiveness, and suicidal ideations. As the fatigue persists, officers experience a deficit in their performance, health, and safety, which generates even more stress in a vicious cycle (Vila, et al., 2002).

As this cycle continues, officers experience burnout which is characterized by exhaustion and increasing cynicism (Violanti et al., 2018). Burnout can also lead to emotional detachment and a distrust of administrators (Gau et al., 2013).

Organizational Stress.Research indicates that the majority of law enforcement officers who experienced a life-threatening situation (occupational stress) felt abandoned by their department administrators during their recovery (Plaxton-Hennings, 2004). These feelings of administrators being unsupportive and unresponsive only served to exacerbate the officers’ pre-existing organization stress and synergize their occupational stress. In extreme life-threatening situations that resulted in an officer being hospitalized, these feelings were so significant that the officers frequently experienced depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation (Carlier et al., 1997).

These organizational stressors, more so than occupational stressors, have continued to prove more significant in predicting clinical depression, anxiety, and traumatic stress symptoms (Gershon, 2009). In other words, police officer depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide are not primarily driven by traumatic calls, but are instead driven by factors internal to the department or organization (Chae & Boyle, 2013). These studies suggest that while the initial incident likely induced negative reactions in the officers, the most significant byproducts of these events were feeling abandoned by the department.

Mitigation

Literature surrounding law enforcement training is clear that with the increasing difficulties of an officer’s responsibilities, additional in-service training is critical (Gillet, 2013). Training practices and theories have also changed considerably through the history of policing so that current training should be based on a mix of lecture, discussion, exercises, and reflection in order to include multiple learning domains (Schafer, 2010). Specific to stress induced suicidal ideation, studies have shown that various protecting factors are affective, such as active coping, being familiar with community resources and identifying social support systems (Chae & Boyle, 2013, Allison et al., 2019). Furthermore, law enforcement agencies that implement effective intervention and prevention programs that support and train around these protective factors may decrease stress and suicidal ideation (Chae & Boyle, 2013). This is good news for organizational development consultants because it means that interventions can have a positive effect in mitigating the law enforcement suicide crisis.

Theory to Practice Application

Several Organizational Development theories can be applied to the entire process of assessing and intervening in organizational stress in law enforcement organizations. The full circle of organizational consulting includes “entry, contracting, data gathering, diagnosis, feedback, intervention, evaluation and exit” (Anderson, 2019, p. 119). While the main focus is on interventions, these interventions are critically important because people and processes exist in an interconnected web so one change will have ripple effects through the organization (Anderson, 2019). Additionally, Anderson (2019) notes that a successful team is needed to support success system-wide. These interventions are critical to not only change the culture of law enforcement, but to save lives within that system.

Data Gathering

Beginning with data gathering, “the survey or questionnaire has been one of the most commonly used methods of data gathering” and there are a number of validated law enforcement focused surveys assessing stress (Anderson, 2019, p. 157). Surveys are beneficial because they are low cost, easy to administer, and allow for anonymity. They also allow the results to be tracked and analyzed over time. One such survey is the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Questionnaire (Radloff, 1977). The Spielberger Police Stress Survey (Spielberger et al., 1981) is another useful tool in tracking police stress over time. Most large organizations use some form of survey as a common strategy, and police departments should be no different (Anderson, 2019).

One of the challenges with surveys, especially recurring surveys over time, is the perception that nothing is changing. Line level employees and managers alike may become frustrated with their perceived lack of progress and the consultant’s perceived sole focus on collecting data. As Anderson (2019) notes, “a consultant who spends time with surveys, conducting interviews, giving feedback, or facilitating meetings may appear to be producing very little and taking a long time to do so” (p. 60). Therefore, the consultant needs to find a balance in initiatives other than surveys to ensure employees and supervisors are perceiving forward progress instead of stagnation.

Interviews could also be used to gather data, but may not be practical for gathering the initial data. Interviews, generally one-on-one conversations with organizational members, can be very time consuming to plan, conduct, and analyze (Anderson, 2019). The interview results can also be difficult to track over time because of the investment required to conduct them. In the specific case of law enforcement, police officers are naturally suspicious and may not open up to interviewers. This concern may be mitigated if the researcher is also a police officer since same-group members may be less threatening (Rubin & Rubin, 2012).

Data Analysis

Once gathered, the data can be analyzed through various models. One such model is Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid, which has two axes labeled “concern for production” and “concern for people” (Anderson, 2019, p. 33). On this grid, each axis ranges from one to nine with nine indicating a high concern in that particular area. Plots are then reported in a one, nine format which corresponds with low concern for production and high concern for people. These values could be obtained through the aforementioned surveys or interviews. Using this Grid may show a correlation, for example, between organizational stress and a perceived lack of “concern of people” (Anderson, 2019, p. 33). Leaders with both high concern for production and a high concern for people are more likely to support the needs of their people to reduce both organizational and occupational stressors. Any associations rendered through this Grid may illuminate and clarify where the organizational consultant should begin investigating a possible intervention.

Schein’s culture assessment (Anderson, 2019) is particularly helpful in analyzing qualitative data surrounding the culture of an organization through focus groups as they generate qualitative data through group surveys. Because groups form culture, it should be the groups, not the individuals who are surveyed (Anderson, 2019). As a group, employees should then discuss and evaluate the group’s culture, its values, and whether the culture and values are hidden. The group can then discuss what change means for the organization and what changes are necessary for the organization to strengthen and achieve its goals.

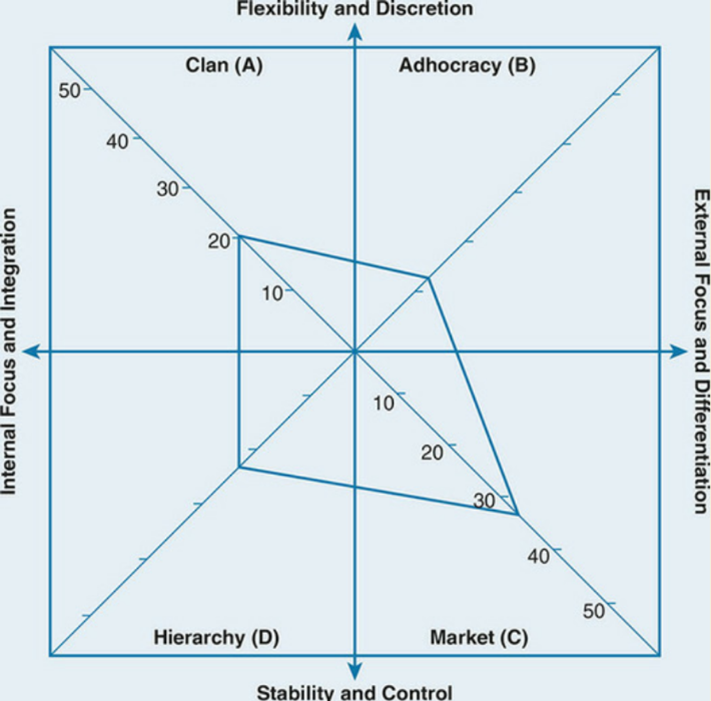

Figure 1 (Anderson, 2019, p. 345)

Figure 1 (Anderson, 2019, p. 345)

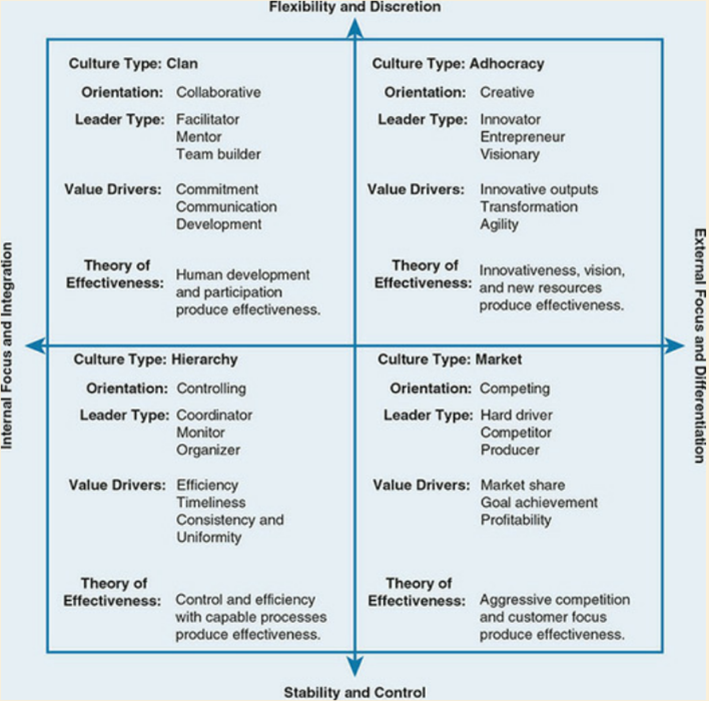

Figure 2 (Anderson, 2019, p. 344)

Figure 2 (Anderson, 2019, p. 344)

Competing Values Framework is a great analysis tool for quantitative data surrounding the culture of an organization (Anderson, 2019). In this framework, individuals complete a survey that rates the organization on two axes of “internal versus external focus and preferences for flexibility or control” (Anderson, 2019, p. 343. These ratings can be plotted on the axes as seen in Figure 1, below. Each resultant quadrant has specific attributes as seen in Figure 2, below.

The Competing Values Framework can be an incredibly helpful tool because each quadrant requires, and responds differently to, change agents (Anderson, 2019). In the context of law enforcement stress, suicide risk and mitigation, these assessments may be highly significant to a police chief in evaluating the culture of their police organization. For example, most law enforcement organizations are likely hierarchical, and may benefit from interventions geared towards bringing them closer to the clan quadrant where mentoring, team building, and human development are more openly supported.

Individual and Group Interventions

Following the data analysis, an array of individual and group interventions can be evaluated, including personality type assessments. “Common individual instruments used in OD engagements are the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, FIRO-B, Thomas-Kilman Conflict Mode Instrument, and DISC, to name just a few” (Anderson, 2019, p. 229). These personality assessments can give insight into how an individual will work by themselves, but also in a group or team setting. A police executive may find that completing these assessments with a group or team could help resolve conflict by evaluating communication preferences, for example. This strategy may also be helpful in creating buy-in from a quiet or detached team member as it ignites their curiosity (Anderson, 2019).

With or without one of the personality assessments discussed above, coaching is another widespread and effective individual intervention. Coaching is usually completed one-on-one to work towards a specific goal or resolution of a given task. There are several different types of coaching including coaching for “skills…performance…development… [and/or] the executive’s agenda” (Anderson, 2019, p. 233). Whereas coaching occurs between two equal individuals, mentoring occurs between a more experienced person and their protégé. Both coaching and mentoring can lead to significant personal development and growth that will allow the participant to better engage in a group or team environment. While police supervisors may benefit from coaches, new officers would likely benefit from culture mentors who help engrain in them a new police culture that, for example, removes the stigma from mental health conversations.

Group interventions, unlike individual interventions, are focused on the team. In law enforcement, there are most commonly self-directed work teams as each patrol shift tends to manage itself. On the other hand, cross-functional teams in law enforcement tend to be ad hoc. For example, when a rash of car break-ins plagues part of a town, the police executive may form a cross-functional team with patrol officers, detectives, data analysts, and crime scene processors. Once the perpetrators are arrested, this team often disbands.

In the process of changing the mental health stigma in law enforcement, a confrontation meeting may be necessary. These meetings are typically four to eight hours and provide an opportunity for the group to confront their obstacles (Anderson, 2019). There are seven phases of a confrontation meeting, including “climate setting…information collecting…information sharing…priority setting and group action planning…organization action planning… immediate follow-up by top team…[and] progress review” (Anderson, 2019, p. 269). Provided that the police executives support the change and hold the group accountable, a confrontation meeting can be highly productive.

Beyond strategic planning, organization-wide interventions include Total Quality Management, Reengineering, and Six Sigma (Anderson, 2019). Total Quality Management involves every employee, from the front line to the executives, evaluating how to ensure quality throughout the organization. Quite simply, “quality is everywhere” (Anderson, 2019, p. 306). Reengineering involves restructuring entire process and organizational components (Anderson, 2019). Six Sigma has to do with how many errors are made per a given period of time. While these three interventions are beneficial for some organizations, law enforcement likely wouldn’t be an appropriate place for them given that their focus is not on profit driving enterprises. By the same token, many interventions that are appropriate for mergers and acquisitions would not be appropriate for law enforcement.

Sustaining Interventions

Regardless of which specific intervention, or combination of interventions is chosen, there are numerous ways to sustain and evaluate the changes. These tools to sustain change include meetings, conferences, reviews, and additional consultations (Anderson, 2019). No matter the specific format, the idea is to gather a group of people and check in to see how the change has impacted the organization. Some organizations use terms like “wins, losses, and neutrals,” while some organizations use terms like “starts, stops, and continues” to highlight and categorize results of the intervention. Finally, one of the most powerful ways to sustain change in an organization is to publicly recognize employees who have made efforts to support the change and move the organization forward. In the context of law enforcement, this may mean publicly recognizing an officer who speaks up about mental health, both internal and external to the department. Rewards could also take the form of a paid day off following a voluntarily mental health evaluation. The idea is to create incentives that push the organization towards the change.

Part of sustaining a change also includes evaluating it to determine if the organization wants to sustain that change. In other words, to determine if the change supports the organization’s new values and mission. Evaluating a change provides an opportunity for stakeholders to enjoy growth and focus by clarifying objectives, for example (Anderson, 2019). A good evaluation will consider both process variables and output variables. The resulting evaluation can take the form of a meeting, PowerPoint, or written report.

Conclusion

The entire cycle of organization development can be leveraged to mitigate law enforcement occupational and organizational stress which is believed to be a contributing factor in suicidal ideation, attempts, and completions. An organization development consultant could gather data in a number of ways utilizing surveys or focus groups. The consultant could then analyze that data in a number of ways to determine an area that needs an intervention. Having identified the need, the consultant could then design an individual, group, or organization-wide intervention. Finally, the consultant could evaluate and sustain that intervention if does in fact move the organization towards its goal. While the specifics of the data gathering, intervention, evaluation, and sustainment would likely be different at police departments across the country, the fact that police departments could benefit from an organizational development intervention is nearly universal.

References

Anderson, D. L. (2019). Organization development: The process of leading organizational change. Sage Publications.

Allison, P., Mnatsakanova, A., McCanlies, E., Fekedulegn, D., Hartley, T. A., Andrew, M. E., & Violanti, J. M. (2019). Police stress and depressive symptoms: role of coping and hardiness. Policing (Bradford, England), 43(2), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/pijpsm-04-2019-0055

Carlier, I., Lamberts, R. and Gersons, B. (1997), “Risk factors for posttraumatic stress symptomology in police officers: a prospective analysis”, The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185, 498-506.

Chae, M. H., & Boyle, D. J. (2013). Police suicide: Prevalence, risk, and protective factors. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 36(1), 91-118.

Denhardt, R. B., Denhardt, J. V., Aristigueta, M. P., (2016). Managing Human Behavior in Public and Nonprofit Organizations. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Gau, J. M., Terrill, W., & Paoline III, E. A. (2013). Looking up: Explaining police promotional aspirations. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(3), 247-269.

Gershon, R.M., Barocas, B., Canton, A.N., Li, X. and Vlahov, D. (2009), “Mental, physical, and behavioral outcomes associated with perceived work stress in police officers”, Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 275-289.

Gillet, N., Huart, I., Colombat, P., & Fouquereau, E. (2013). Perceived organizational support, motivation, and engagement among police officers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(1), 46.

Papazoglou, K., Koskelainen, M., Tuttle, B. M., & Pitel, M. (2017). Examining the role of police compassion fatigue and negative personality traits in impeding the promotion of police compassion satisfaction: A brief report. Journal of Law Enforcement, 6(3), 1-14.

Plaxton-Hennings, C. (2004), “Law enforcement organizational behavior and the occurrence of posttraumatic stress symptomology in law enforcement personnel following a critical incident”, Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 19, 53-63.

Queiros, C., Kaiseler, M., & Da Silva, A. L. (2013). Burnout as a predictor of aggressivity among police officers. European Journal of Policing Studies, 1(2), 110-135.

Radloff, L.S. (1977). The CED-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-40

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2012). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Russell, L. M., Cole, B. M., & Jones III, R. J. (2014). High-risk occupations: How leadership, stress, and ability to cope influence burnout in law enforcement. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 11(3), 49.

Schafer, J. A. (2010). Effective leaders and leadership in policing: traits, assessment, development, and expansion. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. doi: 10.1108/13639511011085060

Spielberger, C. D., Westberry, L. G., Grier, K. S., & Greenfield, G. (1981). The Police Stress Survey: Sources of stress in law enforcement (Monograph Series Three, No. 6). Tampa, FL: Human Resources Institute, University of South Florida.

Vila, B., & Kenney, D. J. (2002). Tired Cops: The Prevalence and Potential Consequences of Police Fatigue. National Institute of Justice Journal, 248. doi:10.1037/e527842006-003

Vila, B., Morrison, G. B., & Kenney, D. J. (2002). Improving Shift Schedule and Work-Hour Policies and Practices to Increase Police Officer Performance, Health, and Safety. Police Quarterly, 5(1), 4-24. doi:10.1177/109861102129197995

Violanti, J. M. (2004). Predictors of police suicide ideation. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 34(3), 277-283.

Violanti, J. M., Mnatsakanova, A., Andrew, M. E., Allison, P., Gu, J. K., & Fekedulegn, D. (2018). Effort-Reward Imbalance and Overcommitment at Work: Associations With Police Burnout. Police quarterly, 21(4), 440–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611118774764

Violanti, J. M., Mnatsakanova, A., Burchfiel, C. M., Hartley, T. A., & Andrew, M. E. (2012). Police suicide in small departments: a comparative analysis. International journal of emergency mental health, 14(3), 157–162.

Violanti, J. M., & Steege, A. (2021). Law enforcement worker suicide: an updated national assessment. Policing: An International Journal, 44(1), 18-31. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM0920190157

Leave a comment